In June 2018, Germany were very close to qualifying for the World Cup. In June 2019, Germany have been relegated to the European 3. division. It’s been a rollercoaster year

for the DRV XV and quite frankly I still wonder why the relegation happened. I’ve collected some numbers from 5 matches of the REIC 2018/19 in order to provide additional insight

as to why Germany finished the season with zero wins.

I suspected that the troubles had primarily originated on the offensive side of the ball. The data led me to believe that indeed the Black Eagles had been much stronger in defending

than in attacking. In bullet points Germany suffered mostly from [1] the lack of clinical finish [2] lack of ‘standard’ line-breakers, and [3] difficulties with moving the ball

forward. It seems like the game plan included surrendering possession, defending ferociously, and patiently waiting for opposition errors. That was a good plan, but – as I found out –

with only 9% plays resulting in entering the opp22 zone, Germany scored too few points to successfully compete against other European T2 countries.

Ball Carrying

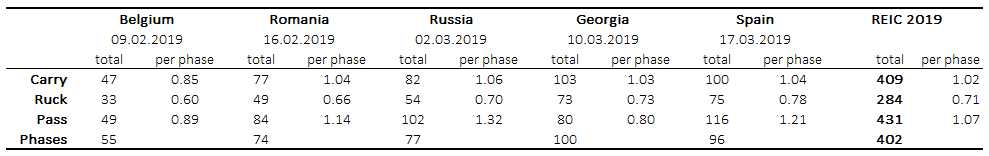

The best way to describe the German offence 2019 is power-running. In five matches of the REIC regular season the Black Eagles carried the ball 409 times, averaging 1.02 carry per phase.

A bit surprising was the fact that despite the power-running, they recorded only 284 attacking rucks (0.71 per phase). The table below summarises carries, attacking rucks, and passes.

The numbers are alarmingly low for the total mess-of-a-match opener against Belgium, when Germany simply surrendered possession and let the opposition attack. The total of 33 attacking

rucks looks disappointingly low when compared to the Belgians’ 110. And so do the 0.36 carry-to-tackle ratio (47 carries/131 tackles), nearly two-times lower than it was against much

stronger defences (Romania: 0.56, Georgia and Spain: 0.70, Russia 0.71).

Germany’s most effective weapon were the forwards. Let’s take a closer look at carries against Romania. Out of the total 77 carries, forwards accounted for 39 (51%) of them. Excluding

carries that occurred directly after kick receptions or interceptions (of all kind), the percentage increases to 54%. Interestingly, Tobias Williams (loosehead prop) and Eric Marks

(lock) recorded 7 carries each, whilst the inside centre carried the ball 6 times. In terms of ball-carrying forwards, Germany have met the T1 standards, at least quantitatively.

Below is an example of how Germany utilised their forwards, running a 1-3-3-1 system.

After the ball is passed to Schulte, the fly half drifts towards the second 3-man pod. He waits until Emil Rupf (6) and Jörn Schröder (4) engage the Romanian defenders, continues

running east-west and finally passes the ball to Kurt Haupt (2). The German hooker breaks the tackle and offloads the ball to Felix Lammers, who is tackled a few metres behind

the gainline. This rather impressive play ended up exactly as so many other plays have during the REIC19 campaign – with a turnover.

After the relegation many players have called it a career. In the upcoming REIC we won’t be watching Tobias Williams’ line breaks or Kurt Haupt’s offloads. Will the attacking plan

change? Perhaps, but other effective ball carriers like Eric Marks or Jacobus Otto, a very mobile flanker, have been selected by the head coach Mark Kuhlmann. (According to the

DRV website, however, neither of them will play against Poland on 2. of November.).

Phases

Teams surrendering possession or/and relying more on their defensive rather than offensive skills do not produce lots of phases. Take for instance England and Australia in the RWC

quarterfinal. Attacking metrics were clearly in Australia’s favour (62% possession, 2 times more metres and carries; source:

ESPN Scrum), and obviously the Wallabies produced more phases per attack than England

(3.7 and 2.3, respectively; source:

Rugbycology).

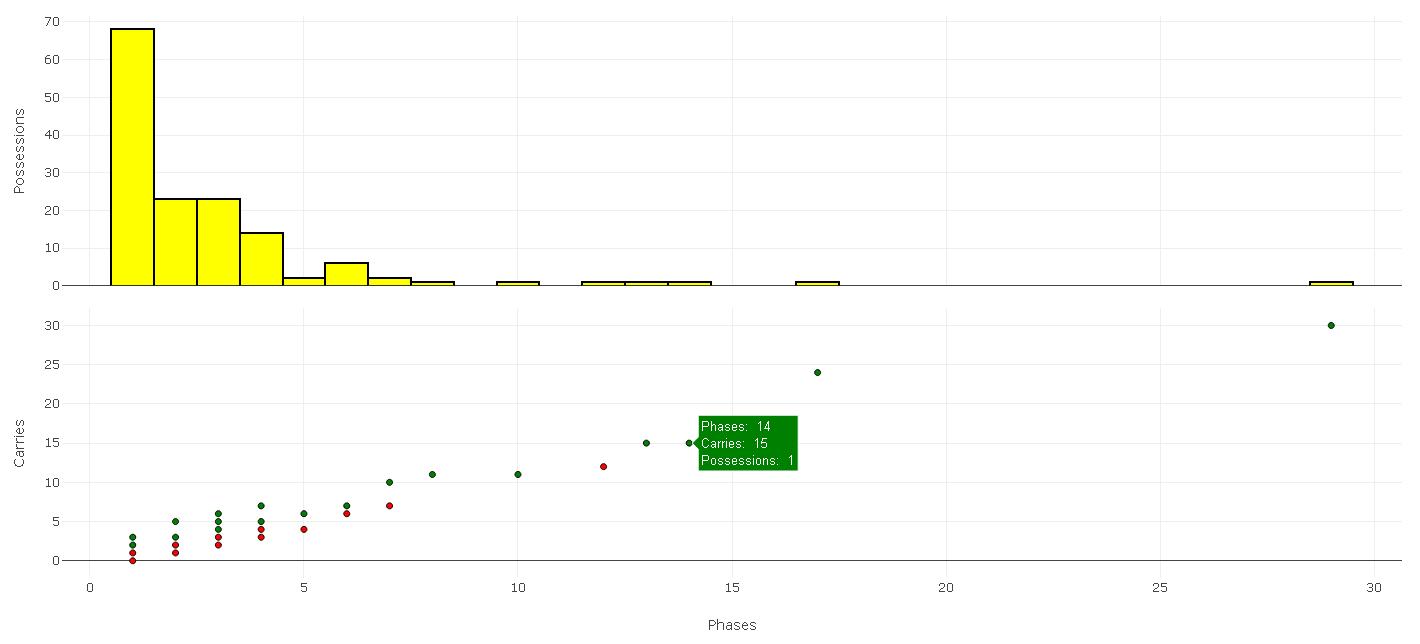

The aggregate numbers locate Germany somewhere between England and Australia. With 145 possessions and 402 phases, the average result is equal to 2.77. The median is much smaller (2),

suggesting that the distribution of phases per possession is highly skewed to the right. The upper panel of the figure below indeed shows a very long right tail. This by no means is strange -

kicking for territory alone forces the opposing team to kick back, generating a vast amount of one-phase possessions. Stats nerds may enjoy the fact that the skewness coefficient

estimated for the phases/possession was indeed large and positive (4.42).

Additionally, I added a scatter plot depicting the carries per phase. Hover over the surface to find out how many times a specific combination has occurred. All combinations with

more carries than phases are marked green. Nearly 15% of possessions finished without a single carry. Every fourth possession fell into the one-carry-one-phase bin.

How the Ball Travelled

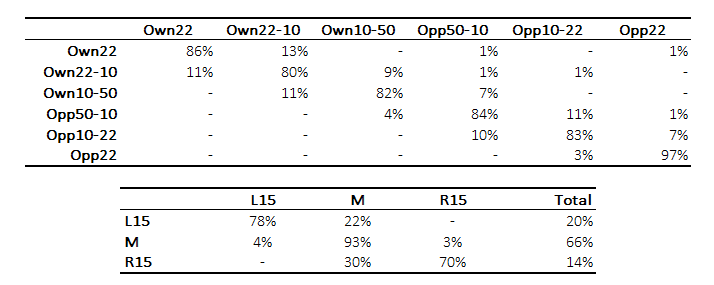

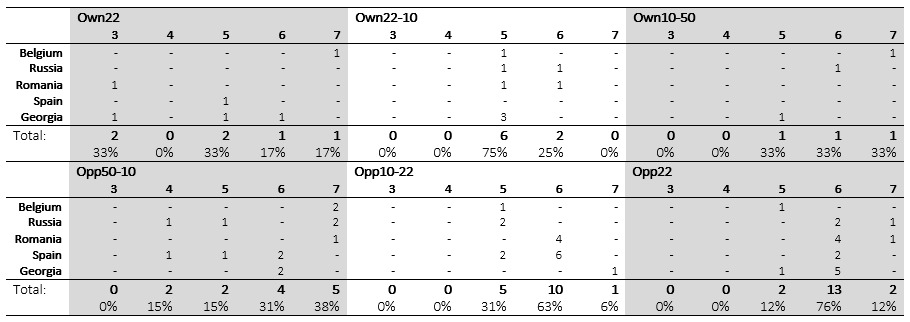

The tables below summarise how the ball travelled across the vertical and horizontal zones. I located passes, carries, rucks, and tactical kicks in 6 vertical zones (own22, own22-10,

own10-50, opp50-10, opp10-22, opp22) and 3 horizontal zones (left 15-metre channel, right 15-metre channel, and the space between them). For the sake of simplicity, let’s call the

passes, carries, rucks, and kicks plays.

How to read the information provided by the tables? The percentages on the main diagonal element of the table show how many times a play started and finished in the same zone.

For instance, if a play started in the own10-50, the chance to stay in this zone was equal to 82%. This is a relatively short zone, but the ball moved forwards in only 7% of all plays

starting in it.

For a team often surrendering possession, escaping from own22 is vital. Again, the percentages achieved against specific opponents are counter-intuitive. When Germany played the

East-European powerhouses, Georgia and Romania, the chance to move forwards from the own22 was large (21% and 22%, respectively). Against Belgium and Spain, the probability declined

below 10%.

The distribution of plays by vertical zones, particularly the attacking rucks, also depicts the offensive strategy aiming at moving the ball as far from Germany’s own territory as

possible. Of the whole of 284 attacking rucks, 61% occurred in the opposition’s half. Unfortunately, the Black Eagles lacked the necessary clinical finish. When hosted by the Lelos,

Germany performed astonishing 64% of all attacking rucks within the opp22. They also recorded 51% of carries and 34% of passes in the Georgia’s red zone. Alas, without touching the

ball down.

Defence coaches are often interested in frequencies with which the opposition uses specific horizontal channel. My standard routine is to cut the pitch into 6 zones, but the poor quality of

home-game footage forced me to stick to 3 zones. Out of the total 1080 plays, Germany finished 198 plays (25%) in the left 15-metre channel and 128 plays (12%) in the right 15-metre

channel.

The ‘persistence’ of the middle channel seems to be yet another result of the power-running. Once the ball moved into the middle of the pitch, the chance for the ball to travel to the L15 or R15 channels

were minute. But if the lion’s share of the carries is performed by the forwards, the outside channels lose their importance.

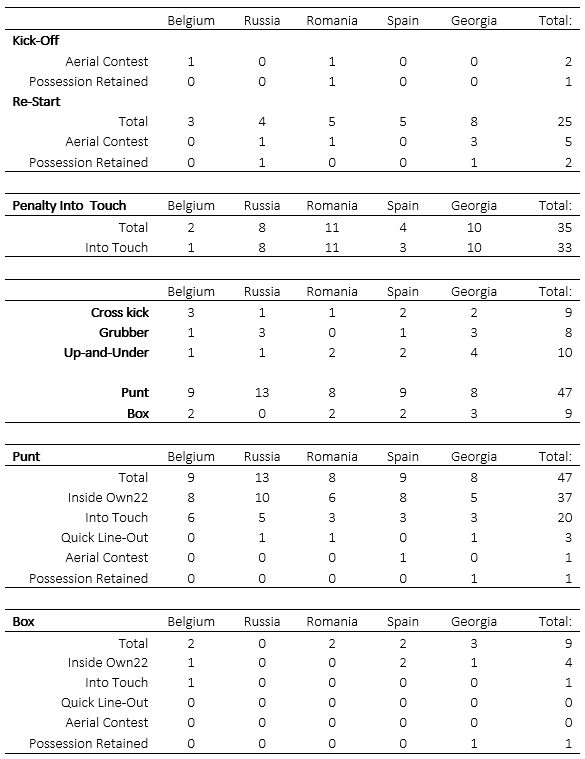

Tactical Kicking

What separates T1 from T2 is the tactical kicking, and every side with T1 ambitions ought to master it in a double quick time. The cross kick became a powerful weapon for Japan. In

three matches of this year’s Pacific Nations Cup (USA, Fiji, Tonga) the Brave Blossoms used it 13 times, retaining possession 6 times. The stats for Germany look much less optimistic.

9 cross kicks in 5 matches is not exactly a T1 standard. In fairness to the Black Eagles, they utilised up-and-unders and grubbers more often than Japan. The tables below summarise the

frequencies and results of kicks from hand.

Too few kicks led to aerial contests, let alone to retaining possession. The latter occurred only 6 times in 83 attempts (9 times in 113 attempts including kick-offs and re-starts).

Raising the former, aerial contest was an equally rare event. 7 out of 8 challenges in the air resulted from kick-offs and re-starts. Clearly, this is an area where Schwarze Adler need

to be more effective.

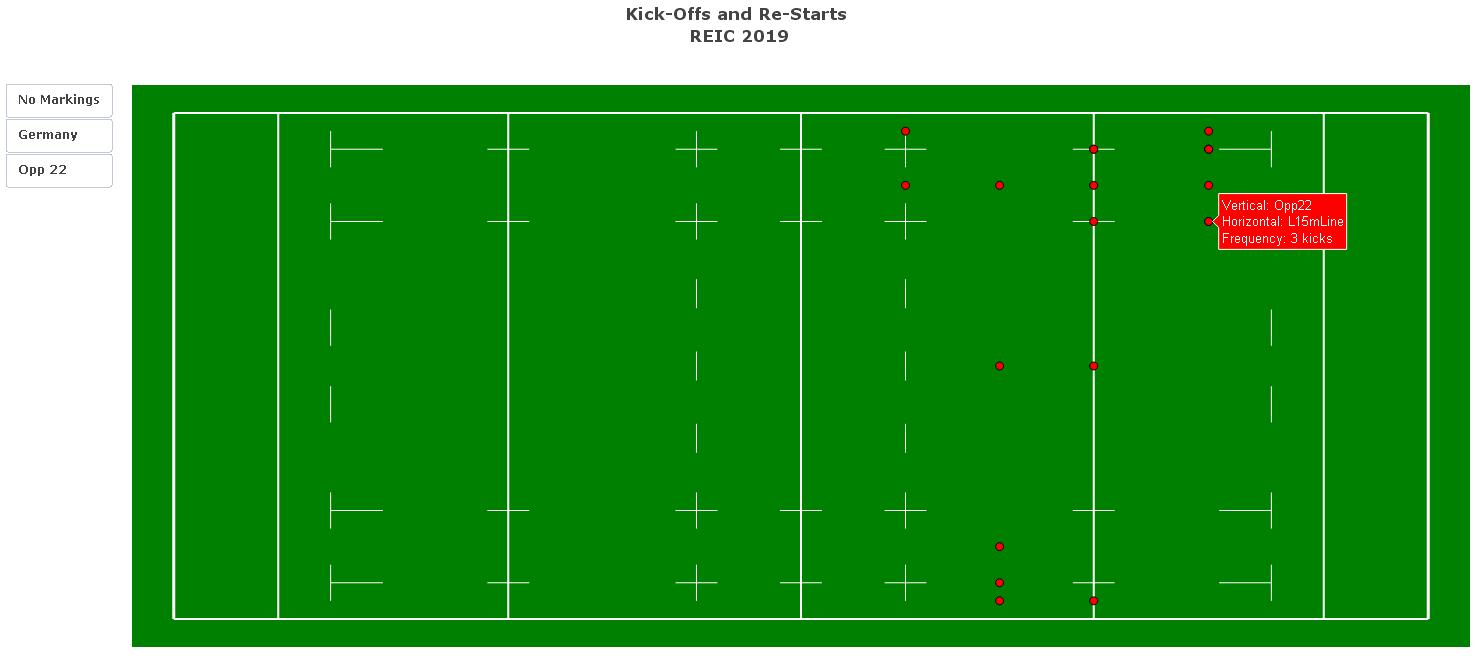

Another distinctive feature of Germany’s kicking was a low number of box kicks. Instead, Germany punted a great deal. And did it in a smart way, too. Nearly 55% of punts found their way into

touch. Equally important was the fact that only 3 punts into touch resulted in a quick line-out. The length of punts was satisfactory as well. When the Black Eagles punted from within their

own22, the ball travelled to the opposition half 20 times in 37 attempts.

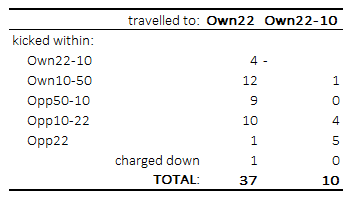

For obvious reason the receiving opponents were much frequently challenged in the air after kick-offs and re-starts. Every fourth kick from the halfway line resulted in an aerial

contest, the possession was retained once. The red dots on the graph below present the area where German fly-halves kicked the ball.

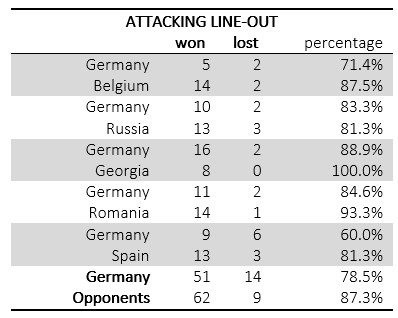

Set Pieces: Attacking Line-Outs

Germany’s attacking line-out performance was worryingly inconsistent. Winning 51 out of 65 own line-outs looks doesn’t look bad, but once the aggregate numbers are broken down by

opponents, the ratio varies between 60% and 89%.

Setting aside the numbers for a moment, some of the line-outs were planned in a very creative manner. A three-man line-out with a quick ball exchange is something that you don’t see

often in REIC tournament. Germany used it twice. Below is the line-out that surprised the Romanian defence. A direct pass and a quick return pass to the hooker, who by the way runs

impressively fast, could have damaged the defence. Unfortunately, the return pass went forward.

Germany utilised this interesting concept also in other set-ups. There’s a six-man line-out with a dummy-jumper deep within the Georgia’s own22-zone. Felix Mertel (7) goes full speed

through the huge gap between the first player and the lifter.

Had the defenders followed the jumper, nobody could have stopped Mertel. But the Lelos covered ground rather than challenged the jumper in the air, so the German ball carrier hit the

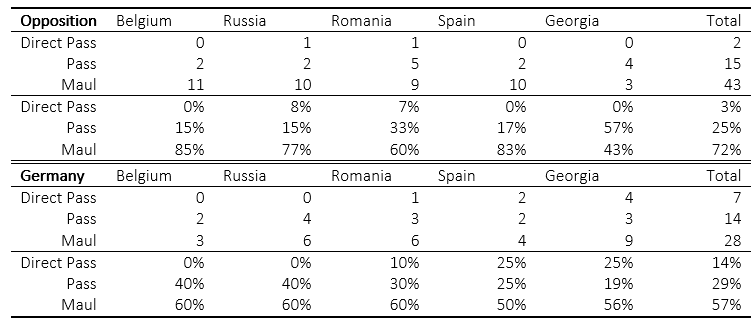

wall of Georgian defenders. Even though the line-out resulted in a dominant tackle, the concept itself may create a mismatch. After the line-out, Germany opted for a maul with 57%

frequency (see the table below for further details). Obviously, within the opp22 the percentage was even higher – 31 attempts (100%) lead to a maul, so a maul was expected after this

line-out as well. To disrupt the timing in the early stage of the maul, the defending team may decide to jump, hence leaving the ground uncovered. And that was what the German offence

gambled on.

The last table in this section summarises the personnel. Interestingly, the Black Eagles also used a 3-man line-out.

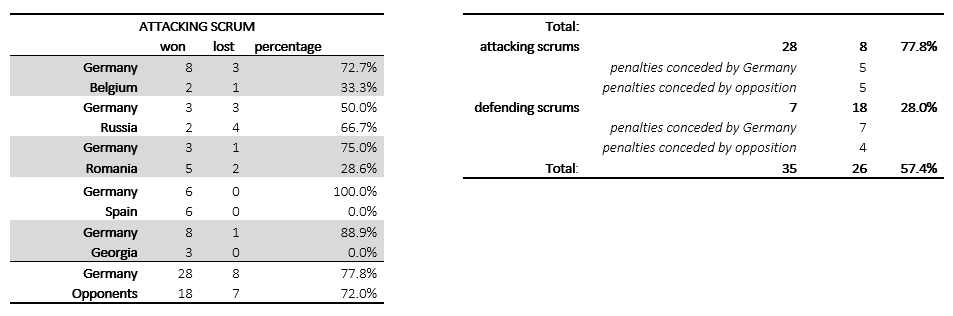

Set Pieces: Attacking Scrums

Even though Germany is not renown for a dominant scrum, their scrummaging is smart enough to challenge much stronger teams. If there were troubles up front, the ball escaped the scrum

quickly. The majority of scrums resulted in a ground pass, usually performed by the scrum half. But when there were troubles up front, N8 passed more often than the scrum half.

Pick-and-go was not in Germany’s standard repertoire (5 out of 23 attacking scrums), but again, when there were troubles up front…

Once again the scrum stats reveal the major problem Germany have struggled with the entire season – inconsistency. Winning more defending than attacking scrums against Russia or

achieving higher winning percentage against Georgia than Belgium is the best indicative of inconsistency. I daresay it was the inconsistency in almost all aspects that costed Germany

dearly.

Tackling

It’s perplexing that a team completing 88% of all tackles has lost all REIC matches. Even more astounding is the TCR that Germany recorded against Russia – 97%. Have you ever heard of

a match when the defence missed as many tackles as it conceded tries? Here it is, 4 tackles missed, 4 tries conceded. A nightmare for defensive coaches as well as for the analysts. The

table below shows the tackling statistics by opponent and vertical zone.

Many of the missed tackles went unpunished. Here’s an example from the Spain match, where Vito Lammers successfully chased the ballcarrier. Even though the German outside

centre missed the tackle, he kept his outside shoulder free, containing Victor Sanchez to the inside. And help always comes from the inside.

Not only the Black Eagles tackled successfully, they also performed a fairly large number of dominant tackles. I understand that a T1 fan would not call the average of 12 dominant

tackles per match 'a lot', especially after witnessing England’s 46 against Ireland. To offer an example from the same tier, in November 2018 Poland completed only one dominant tackle

against the Netherlands.

Defending Driving Maul

Defending the driving maul was an area where the German defence performed rather poorly. The gif below shows how Romania utilised the maul in Germany’s own22 and created a 2-on-2

situation with a lot of space to cover for the defence.

The opposing teams must have quickly realised that maul could give them an competitive advantage. If you scroll up a bit and inspect the numbers in the table summarising the plays

after line-outs you’ll see that 72% of line-outs resulted in a maul. Particularly Spain gained a lot of yardage due to mauls like the one in the 13. minute of the second half, when

Spain were awarded a line-out near Germany’s 10-metre line. Los Leones formed a maul, exactly like after 5 previous attacking line-outs, and drove it for 24 seconds gaining almost 20

metres.

Defensive Rucks

The modern defence is not complete without players hounding opponents at breakdown. Despite the striking inconsistency (the REIC opener against Belgium again), counter-rucking was an

important aspect of German defence. The Black Eagles attended 253 out of 513 rucks. Adding a little more T3 context to these numbers, in the Rugby Europe Trophy 2018/19, Polish

defenders attended ca. 40% of rucks.

Direktaufstieg

There’s a term in the German language that relegated

Fußball teams often abuse in order to create an illusion of confidence and power:

Direktaufstieg, the direct

promotion. The German RFU officials don’t use this term. Mark Kuhlmann believes Germany is an underdog whilst the strongest team in the competition are the Netherlands. Asked if

Germany were the favourite in the upcoming match against Poland, Kuhlmann replied:

“Perhaps not. Poland are a classic East-European team, very strong and physical. Apart from the front-rowers, we’re going to deal with some disadvantages.

The next two encounters will decide whether or not a

Direktaufstieg would be possible. And whether or not Mark Kuhlmann was just bluffing.

Disclaimers

[1] I do not own the rights to the footage used in the animated gifs. The gifs are purely for non-profit, educational purposes. Visit Rugby Europe's website to watch

all previous matches [2] For line-ups, I used information appearing in the official game sheets published on the Rugby Europe's website. If the player names are not correctly

matched with positions, please let me know and I will update the text immediately.